Welcome to Laboratory of Social Learning & Cultural Evolution

Human Social Learning & Culture Lab:

We perform large scale experiments in virtual words to study how group of people learn to improve their collective action

2023-2024:

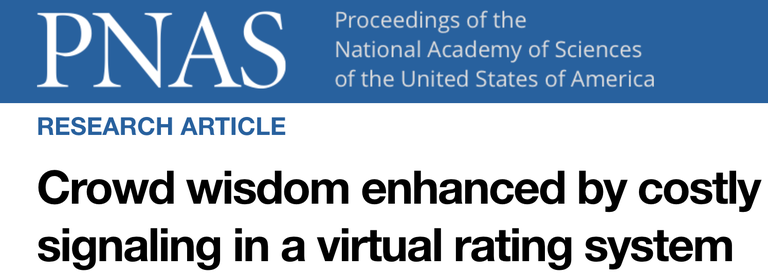

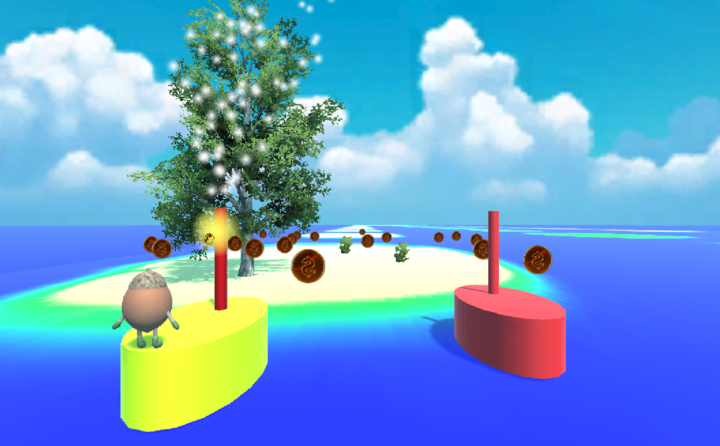

Collective intelligence challenges are often entangled with collective action problems. For example in the case of voting, rating, and social innovation. Due to the cost of individual contributions, people often free-ride on the information contributed by others. The upshot of our findings is a cruel irony: the folks least likely to participate for the collective good are the ones we most need due to their superior skills… Below we describe how we came to that conclusion. We developed a 3D virtual world where online players enjoyed a limited amount of time to collect coins on tropical islands. In the game, ferries that take players from island to island all travel at different speeds, some fast and some slow.

The game included a rating system so players could help each other choose the fastest ferry, and the ratings were the game’s shared resource. Some participants rated most or all of the ferries, contributing to the public good, while others hardly rated any. We found that rewarding people for contributing to a virtual public good improved its quality. The broader diversity of motivations to contribute improved the value of the public good overall. We used a Unity interface combined with our experimental platform www.psynet.dev to run seven variants of the experiment and collect data from 721 players with over 15K decisions. Our results demonstrate the promise of large-scale online experiments to contribute to the understanding of collective intelligence challenges that are entangled with collective action problems.

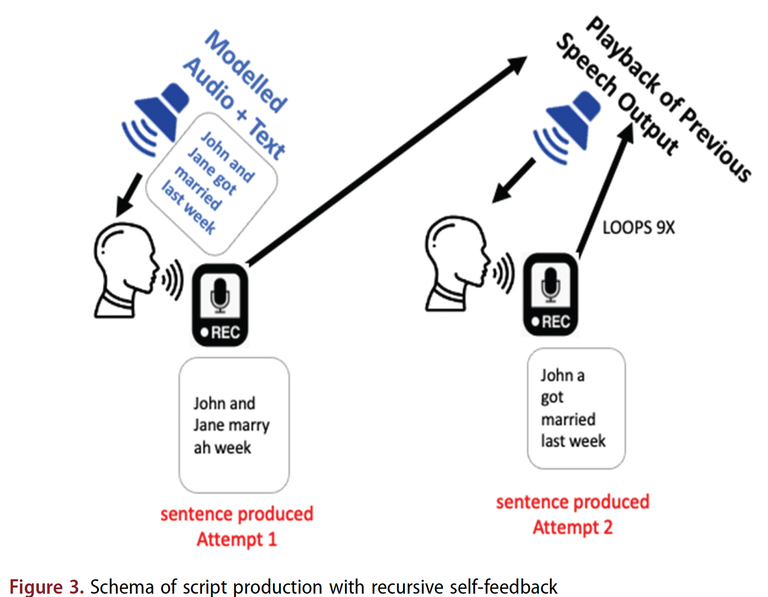

Recursive Self-feedback Improved Speech Fluency in Two Patients with Chronic Nonfluent Aphasia

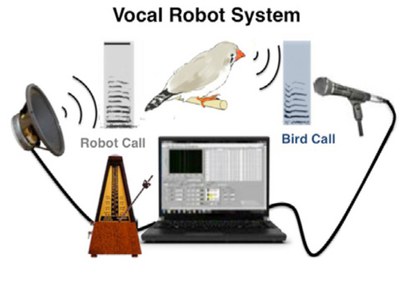

The first author, Gerald Imaezue, did this study as part of his PhD, his advisors were the aphasiologist Mira Goral and I. In this collaboration, Gerald implemented the recursive self training technique we developed to self-train zebra finches with their own song, to treat people with aphasia.

2021:

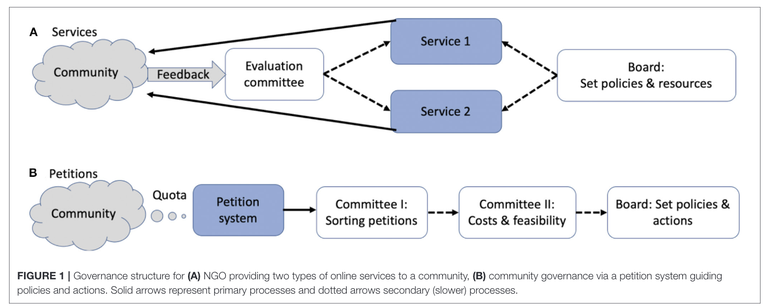

Experimenting with online governance

We developed virtual worlds experiments for studying social feedback

Collaborators: Dalton Conley, Nori Jacobi, Seth Frey

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2020:

A Rating Method for Improved Accuracy of Customer Evaluations and Cost Savings

Collaborator: Dalton Conley (Princeton University)

2019:

In a virtual world experiment we found that costly signaling helped obtain reliable crowd estimates of quality

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Birdsong Social Learning & Culture Lab:

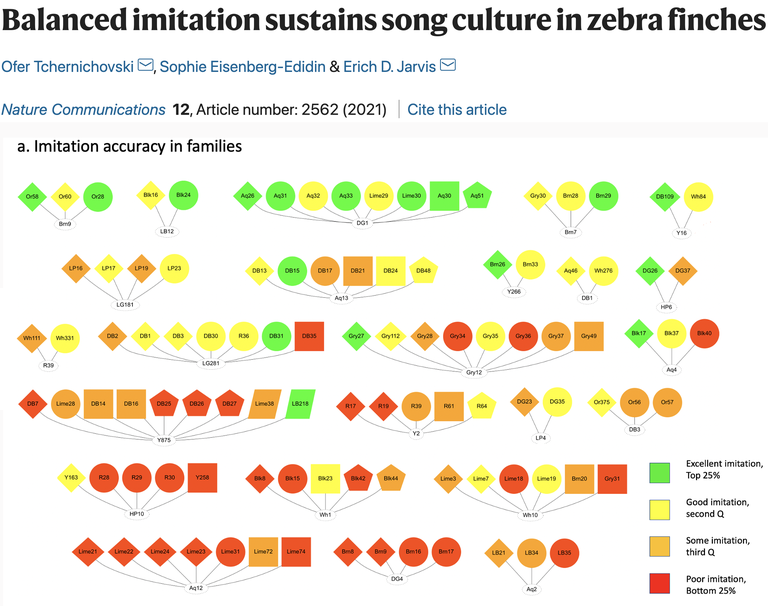

Balanced imitation and song culture Nature Communications article (2021)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Categorical rhythms in thrush nightingales and music are similar

Sexual dimorphism in striatal dopaminergic responses promotes monogamy in social songbirds

We found that the dopaminergic reward circuitry of zebra finches can simultaneously promote social cohesion and breeding boundaries. Surprisingly, in unmated males but not in females, striatal dopamine neurotransmission was elevated after hearing songs. Behaviorally too, unmated males but not females persistently exchanged mild punishments in return for songs. In females, we observed song reinforcement exclusively to the mate’s song. These findings suggest that song-triggered dopaminergic activation serves a dual function in social songbirds: as low-threshold social reinforcement in males and as ultra-selective sexual reinforcement in females. Co-evolution of sexually dimorphic reinforcement systems can explain the coexistence of gregariousness and monogamy.

The forebrain song system mediates predictive call timing in female and male zebra finches

Zebra finches can quickly learn to modify the timing of their innate calls. Using vocal robots, we show that birds can dynamically adjust call timing in anticipation of complex rhythm patterns. Interestingly, non-singing female zebra finches exhibit better learning than male, when interacting with vocal robots. In both females and males, the song system is necessary for predictive call timing and precision. We propose that the song system is a general-purpose commination system: in the case of calls, it enables plasticity in vocal timing to facilitate social interactions, whereas in the case of songs, plasticity extends to developmental changes in vocal structure.

Learning vocal sequences: a comparative study across songbirds and human infants

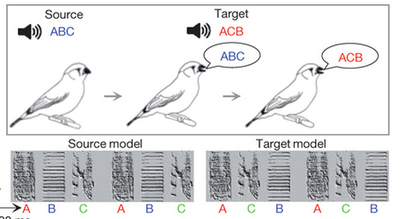

Both birdsong and human language rely on the ability to arrange syllables in new sequences. We developed an experimental technique for presenting zebra finches with sequence rearrangement tasks:

We can now ask the bird: can you swap the order of these sounds? Can you insert this syllable into that string? Birds were able to solve these tasks, but never in a single step. Instead of swapping syllable order or inserting syllables into strings, the birds solved those tasks in a series of steps, gradually approximating the target syntax. For example, to transform the song ABC-ABC to ACB-ACB, the bird learns one transition, say CB (and sings ABCB-ABCB for awhile), a few days later it might learn a second transition, say AC. Finally, once the bird learned the third transition BA, it promptly switches to the target ACB-ACB song, and will never sing ABC again. We found that Bengalese finches learn their more complex song in a similar manner. Strikingly, human infant babbling also develops in a similar manner: each uttered syllable is first performed singly, reduplicated, or at an utterance edge. Then, over 20 weeks or so, the new syllable type gets connected to other syllables in a stepwise manner. Eventually, the infant can babble 'freely' but this is not the starting point of vocal learning -- it is an endpoint of an elaborate developmental process, where combinatorial abilities are gradually acquired. This slow process can explain the developmental gap between the early perceptual capabilities to perceive complex vocal sequences, and the delayed motor capabilities of producing them.

Click here to watch a short movie demonstrating the effect

Click here to read our Nature paper about the development of vocal combinatorial abilities in songbirds and human infants

Vocal exploration is locally regulated during song learning

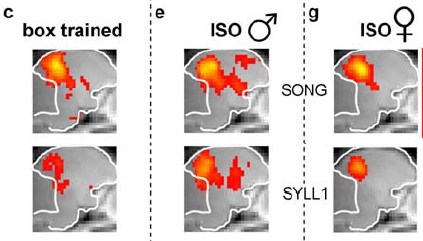

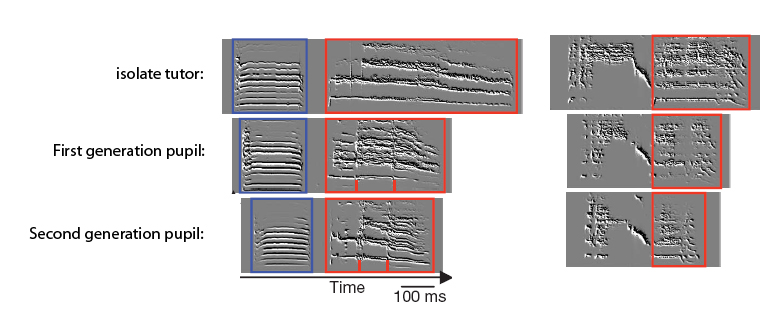

Images of song perception: How early auditory experience shapes auditory fMRI responses in songbirds

Juvenile male zebra finches develop their song by imitation. Females do not sing but are attracted to males’ songs. With functional magnetic resonance imaging and event-related potentials we tested how early auditory experience shapes responses in the auditory forebrain of the adult bird.

Adult male birds kept in isolation over the sensitive period for song learning showed no consistency in auditory responses to conspecific songs, calls, and syllables. Thirty seconds of song playback each day over development, which is sufficient to induce song imitation, was also sufficient to shape stimulus-specific responses.

Strikingly, adult females kept in isolation over development showed responses similar to those of males that were exposed to songs. We suggest that early auditory experience with songs may be required to tune perception toward conspecific songs in males, whereas in females song selectivity develops even without prior exposure to song.

Click here to read Kristen Maul dissertation about how early auditory experience shapes auditory fMRI and ERP responses

Co-authors: Kristen Maul, Henning Voss, Santosh Helekar, Lucas Parra

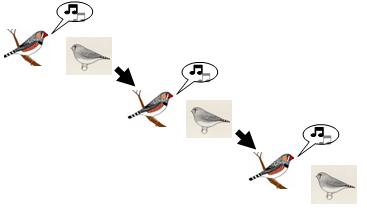

Culture in the lab: development of song culture in the zebra finch

Zebra finch raised in isolation develop abnormal songs. We designed an experiment to determine whether wild-type song culture might emerge over multiple generations in an isolated colony founded by isolates. In tutoring lineages starting from isolate founders, we quantified alterations in song across tutoring generations.

We found that juveniles imitated the isolate tutors but changed certain characteristics of the songs. These alterations accumulated over learning generations. Consequently, songs evolved towards the wild-type in three to four generations. Thus, species-typical song culture can appear de novo.

Click here to download our Nature article about development of song culture

Click here to read Olga Feher's PhD dissertation about song culture

Click here to download examples of song-culture development

How a song is born

Zebra finches learn their song during two months of development (days 30-90 post hatch). Over that time, they listen to adult birds (tutors) and produce 1-2 million song syllables.

We record ALL of them. The images below show the distribution of song syllables during early and late song development. Each dot represents one syllable, presenting the duration of that syllable versus its frequency modulation:

Click here to download our Science article about dynamics of song imitation

Download a movie of syllable types emerging out of an amorphous cloud of undifferentiated sounds (30Mb)

How sleep affects song learning

As mentioned above, zebra finches sing about 1-2 million syllables over song development, or to be accurate, during the days of song development. What do they do over night? Sleep, of course.

But sleep is an active process, and it appears that vocal changes occur during sleep. Those changes are stronger, and qualitatively different than changes that occur during daytime singing.

Our Nature article about how sleep affects song learning

Watch the NOVA Science Now episode about our research